Over the last 20 years, media coverage of climate change has clearly advanced: more news in the media, more specialisation in newsrooms and more journalists covering the issue. However, since 2022, and more markedly in the last year and a half, we are entering a different phase with less media coverage of climate change in general, although there are some exceptions that we will discuss on another occasion.

The issue is losing traction in the media despite the fact that the impacts of climate change are increasing and the scientific evidence is more alarming than ever. The fact is that editors are giving priority to other issues such as geopolitical tensions, the economic crisis and security. Added to this is public fatigue in the face of excessive doom-mongering.

To understand what is happening and why, we propose this necessary reflection because the decline in media coverage of climate change affects the quality of the debate and, ultimately, the ability of governments and society to act.

Here I break down five essential keys to interpreting what is happening.

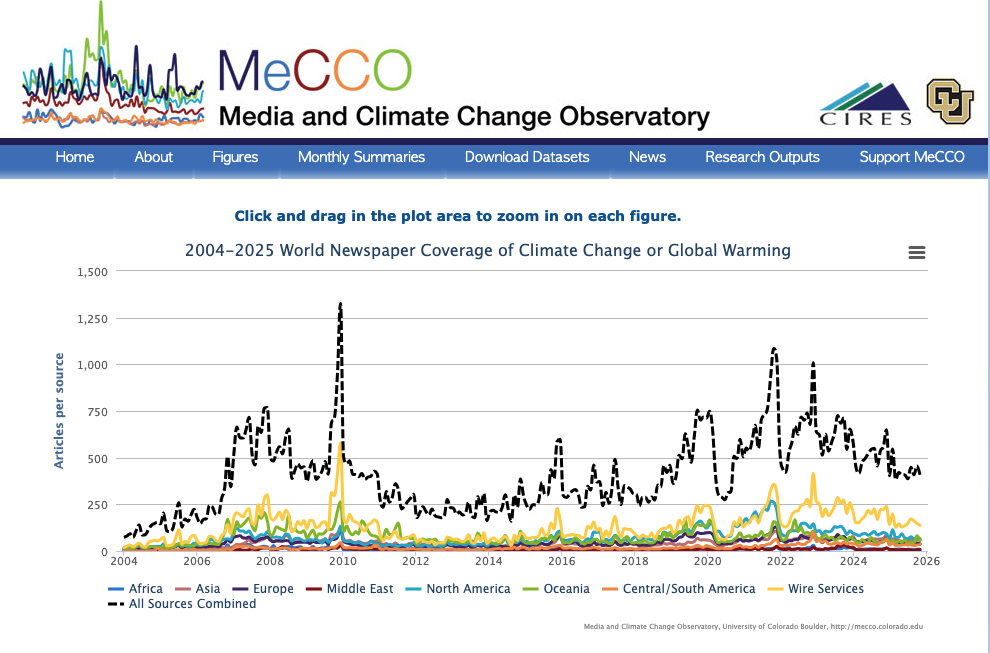

1. After 20 years of growth, the data shows a turning point

Data from the Media and Climate Change Observatory at the University of Colorado Boulder, which analyses 131 media outlets in 58 countries, including Spain, is clear: over the last twenty years, media attention to climate has grown steadily, albeit with ups and downs that coincide with milestones in the multilateral process (such as the COPs in Copenhagen in 2009, Paris in 2015 and Glasgow in 2021), major extreme weather events (such as floods, hurricanes and typhoons) and moments of strong social mobilisation (such as the 2019 Fridays for Future and Extinction Rebellion demonstrations and youth movements).

The COP in Glasgow in 2021 marked one of the strongest upturns after the news blackout during the pandemic. But from then on, we observed a downward trend. It remains higher than before 2018, but it is falling, and falling persistently.

Editors are not giving as much space to climate change, politicians are mentioning it less in their speeches or, when they do, it is as a political weapon, and polls show a decline in public concern for those for whom climate change remains a cause for concern, but less so than the cost of living crisis or security.

2. Less coverage, less concern, less political pressure: a vicious circle that is difficult to break

There is no debate here about whether the decline begins in the media, among politicians or among the public. It is a closed circuit that feeds back on itself.

When the climate loses media space, the public no longer perceives it as an urgent issue. When concern falls, the climate loses political relevance. And when it loses political relevance, the media covers it less.

The result is a vicious circle: less conversation, less research, less follow-up and, therefore, less ability to keep alive an issue that demands continuity. This is particularly serious because climate physics do not wait. While the conversation dies down, the impacts and emissions continue to accelerate.

3. Climate change is becoming an ideological battleground

In the last year, climate change has been absorbed by the dynamics of political polarisation. The most extreme case is the United States, where one’s position on climate is often associated with partisan identity. But in Spain, we are also beginning to see the same patterns: climate, its impacts and its solutions are being used to mark ideological distance.

This politicisation breaks something essential: the consensus around climate science. Science does not veer from one side to the other; politics does. And when climate is read as a sign of political identity rather than a physical phenomenon that affects everyone, the conversation becomes more fragile and volatile.

For journalists, this translates into a more hostile information climate, where explaining what science says can be perceived as ‘political positioning,’ even when it is not.

4. Record emissions and an information ecosystem poisoned by misinformation

While the conversation cools, emissions records continue to rise. 2025 is set to be another record year, with the 1.5 °C limit temporarily exceeded and impacts growing exponentially, not linearly.

And all this is happening in an environment where misinformation is growing rapidly. Social media functions as a largely unregulated space where false content spreads like wildfire. Climate misinformation, in particular, is becoming a structural factor in public debate. And it is not limited to social media: little by little, it is also creeping into some media outlets.

For climate journalism, this means working in a context where clarity is harder to achieve and the noise is louder. And where refutations, although necessary, rarely match the speed of false content.

5. The role of journalism in the era of the ‘wild west’ of information

The United Nations, together with the COP30 Presidency in Brazil, has launched an initiative to defend the integrity of climate information. This is an important step, but it is insufficient without the resources and support of social media platforms and regulators.

The media, on the other hand, can act with immediate impact. In an environment where anyone can publish anything without consequences, journalism becomes a critical tool for defending accurate information: reporting rigorously, contextualising, verifying, refuting, explaining trends and sustaining a reliable public conversation.

We cannot close all the doors to disinformation, but we can strengthen the democratic counterweights that make it less harmful. That is, today, one of the most important missions of climate journalism.

This analysis stems from my speech at the 16th National Congress of Environmental Journalism of the Association of Environmental Information Journalists (APIA) held in Madrid on 26 and 27 November 2025. I am deeply grateful for the invitation and the work of APIA, which is more necessary than ever to uphold rigorous climate reporting in Spain. I hope that this reflection and the debate sponsored by APIA will contribute to broadening an urgent conversation for the future of journalism and climate action. You can watch my full video message here.

If you work in communications, journalism or sustainability and would like to continue the conversation, please email me at mariana@10billionsolutions.com and sign up for our newsletter.