The tide that turned into a tsunami: from fast fashion to ultra-fast fashion

It started a long time ago as a tide: fast fashion brands such as Zara and H&M established themselves as strong favorites amongst buyers looking for very affordable and trendy clothes. The phenomenon was compounded by the exponential adoption of online shopping, to the point that over 20% of clothing sales take place online nowadays – and in the EU, 42% of individuals purchased clothes, shoes or accessories online in 2022. This is oftentimes associated with wasteful habits such as ordering different sizes of an article to try on at home and returning all but one item, multiplying the carbon footprint of deliveries, increasing fast fashion’s climate impacts.

Real-world clothing stores and chains are suffering badly. The tide has turned into a tsunami, with winners being the ultra-fast fashion brands like Shein and Temu, and Amazon. Shein, with its 7,000 new items of clothing posted online every day, and its competitors in the ultra-fast fashion space, continue to gain market share. Thanks to this model of a constantly changing catalog and low prices, Shein and peers appeal to those who, in these times of inflation-pressured purchasing power, want to buy new clothes without sacrificing much on other expenditures, such as housing or digital entertainment subscriptions.

This colossal industry, characterized by its rapid production cycles, endless new collections, and alarmingly low prices, thrives on the constant desire for newness among consumers, encouraging a throwaway culture that is increasingly at odds with the global push towards sustainability and environmental preservation. As Europe leads the charge in implementing robust climate policies and sustainability efforts, the fast fashion industry emerges as a substantial challenge for the continent’s green future.

Grave social and environmental impacts of fast fashion

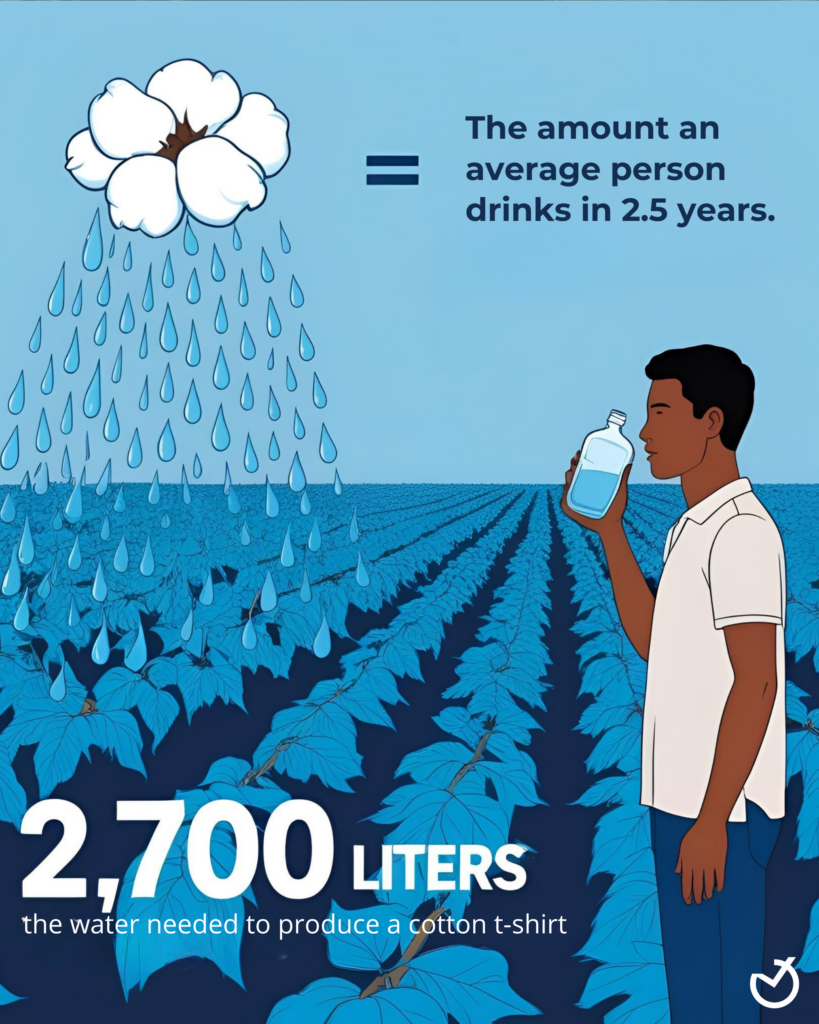

The environmental footprint of fast fashion is staggering, making it a critical area of concern for European policymakers. The industry is one of the largest consumers of water globally, requiring thousands of liters to produce just a single piece of clothing. Moreover, the use of synthetic fibers like polyester, a petroleum product, contributes significantly to the industry’s carbon footprint. The process not only emits a considerable amount of greenhouse gases but also leads to the proliferation of microplastics in our oceans, posing a grave threat to marine life and ecosystems.

The challenge of waste management further exacerbates the environmental crisis. In Europe, millions of tons of textile waste are generated yearly, with a significant portion ending up in landfills or incinerators. This not only squanders valuable resources but also releases harmful pollutants into the environment.

Building levees in Europe against fast fashion’s climate impact

European policymakers have begun to take decisive action. The European Union (EU), for instance, has introduced several initiatives aimed at curbing the environmental impact of the textile industry. The EU’s Circular Economy Action Plan, part of the European Green Deal, aims to ensure that products are designed to be more durable, reusable, repairable, and recyclable, directly targeting the fast fashion model. Moreover, the Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles seeks to improve the industry’s footprint by fostering innovation in sustainable fibers, promoting business models that can extend the life of fashion items, and encouraging more responsible consumption behaviors.

Those initiatives can hardly be successful however, without changing deeply the mindset: regulatory measures need to not only favor but gain momentum through a cultural shift towards valuing quality over quantity, and sustainability over instant gratification. The global nature of the textile supply chain complicates efforts to regulate and monitor environmental standards, necessitating international cooperation and highlighting again the importance of changed consumer behavior.

Trying new measures at national level

As a case in point, France has recently pushed a new bill aimed at abating the fast fashion momentum and the over-consumption fueled by disposable fashion companies – according to Refashion, the Textile, Household linen and Footwear Industry’s eco-organisation, 3.3 billion items of clothing were sold in France in 2022, or 48 per inhabitant. The text, which was examined by the National Assembly on Thursday 14 March, has already received the support of the government.

“Our ambition is to reduce the impulse to buy, which has environmental, social and economic consequences”, Anne-Cécile Violland, the MP who introduced the bill, explains, pointing out that the textile sector accounts for 10% of global greenhouse gas emissions. The bill would include a bonus-malus system and ban advertising. For the moment, only ultra-fast fashion brands such as Shein and Temu are targeted. The text would impose a “penalty of five euros per product for producers who introduce more than 1,000 new models per day”. Between now and 2030, this penalty applied to the company could amount to up to 10 euros per product, with a ceiling of 50% of the pre-tax selling price. This sum will be paid to the Refashion eco-organisation.

On the other hand, so-called “virtuous” companies with limited impact on the environment will be entitled to a “bonus”, also capped at 50% of the sales price excluding tax, paid by Refashion.

In addition, the French Minister for Ecological Transition, Christophe Béchu, announced on Monday 4 March that the government was going to “launch a targeted advertising campaign against short-lived fashion”, in partnership with the French Agency for Ecological Transition (Ademe).

While critics are quick to respond that this text “does not address the environmental impact of fashion, but affects the purchasing power of French consumers”, by discriminating against the lowest incomes, those are certain signs of deep changes in government and citizens’ perception of fast fashion.

By embracing circular economy principles, investing in sustainable technologies, and fostering a culture of mindful consumption with socially just measures, Europe can mitigate the environmental impact of fast fashion and lead the world towards a more sustainable and equitable fashion industry. As for most other climate and environmental emergencies, this is a very tall challenge, but an essential one to tackle.

You can watch Mariana Castaño Cano’s contribution to this issue – in Spanish with subtitles – on the programme En Primera Plana, on RFi. Remember that you can find more news like this in our news section and resources in Academy: